Leah Mellinger was told no. A high school girl in 1990 wasn’t supposed to pole vault. If she wanted a varsity letter in track and field, she had to pick a different event.

Mellinger did. Reluctantly. The Penn Manor grad made herself into a high jumper and eventually qualified for districts.

That decision always stuck with her. It felt unfair to be denied. Years passed, barriers fell and other girls were free to try whatever they wanted.

Mellinger’s chance to pole vault was gone. She decided to never let that happen again. To always chase her dreams, even the ones that seemed a little crazy.

Leah Mellinger stands beside a memorial to Leo Hauck, a fellow Lancaster County boxer and world champion.

That’s how a woman in her early 20s found the courage to step into a ring. It’s how Mellinger became a three-time world champion who was inducted into the International Women’s Boxing Hall of Fame last month.

“Part of me has always been an adrenaline junkie,” Mellinger said. “So if there’s something that kind of scares me, it’s like, ‘I should go do that.’”

The first time Mellinger took a hard punch to the face she cried. That didn’t stop her. She was determined to fight.

A fortunate accident

Mellinger was working for a mortgage company and was traveling the country for real estate auctions after she left college. She found boxing by accident.

It started with a self-defense class. That turned into kickboxing matches. Then regular boxing. Mellinger was terrible at first. She got beat up every day. The instructors were concerned she might quit. That bothered her more than the pounding she took and it forced her to change her approach.

“I was so offended that I stopped trying to do it my way,” Mellinger said. “I started becoming a robot. If they told me to throw a jab, I threw a jab. If they told me to throw a kick, I threw a kick. It really works when you listen to the trainers.”

Martial arts to boxing was a natural transition and the women’s side of the sport was on the rise.

Christy Martin, one of the pioneers, fought on the undercard of a Mike Tyson bout in 1989. Martin’s performance brought her instant celebrity and opened the door for other women boxers.

Mellinger began her pro career in 1996 and retired with a record of 12-5-1. She won three junior-welterweight titles.

“I always had more guts than talent,” she said. “I’m not afraid of failing. Losing a fight is so tough. But you realize the world didn’t end. I learned something. I’ll be better next time.”

Mellinger was a pioneer as well, as she inspired others to try boxing.

Denise Bowers walked into Nye’s Gym one day looking to take her own self-defense class. That’s when she noticed Mellinger wearing a training mask and throwing jabs and hooks. Sweat was pouring down her face.

“She was beating the crap out of all these guys who were taking turns fighting her,” Bowers said. “I remember thinking, ‘That’s who I want to be.’ Seeing her in the ring was life-changing for me.”

Bowers started boxing. She and Mellinger became lifelong friends and longtime sparring partners. They’ve exchanged more punches with each other than any opponent.

Leah Mellinger was 12-5-1 and won three world titles during her boxing career.

Mellinger became fearless. Getting hit in the face no longer fazed her. Nothing did.

“You look down and you’re covered in blood,” she said. “It’s your own blood. I remember thinking, ‘I’m going to the ER after this. I’d rather go with a big gaudy belt than without it. We’re gonna keep fighting.’ You dig down. You find another level.”

The three belts are prized possessions prominently displayed in Mellinger’s home. The only time she took them down from the wall was to bring them to her Hall of Fame induction.

The highest honor

Mellinger’s life has been filled with challenges and apparent contradictions. She was a cheerleader at Penn Manor. The one who threw the other girls in the air. She once entered a beauty pageant and her talent was singing a 1980s power ballad.

If something interested Mellinger, she tried it. She didn’t want to have regrets.

Induction into the Hall of Fame was one of her crowning achievements. She devoted some of her speech to thanking the other women who had the guts to fight and who gave her a bar to try and reach.

Mellinger loved the test boxing presented. She called it “full-contact chess.”

“Boxing is dominating someone physically and mentally,” she said. “There is something to realizing you’ve figured out that puzzle of that person. That you can win because you understand everything.”

Mellinger, 51, retired more than two decades ago. She has survived breast cancer and has reinvented herself as a personal trainer. She has a son and daughter in Lancaster School District.

Aches and pains linger from her fighting days. Arthritis in her hands, wrists and shoulders tell her it’s going to rain without having to check the weather report.

That was the price she paid for her career. For being a champion.

“She definitely left her mark,” Bowers said. “If you live in Lancaster, you know of Leah. She has that reputation of being a title belt holder.”

Mellinger learned she was capable of more than she ever imagined once she stepped into the ring. Those lessons are still with her. They took her to the Hall of Fame. They carry her through her health challenges and being a mom.

“Boxing changed me,” she said. “I have perseverance. I have a level of fight in me that isn’t going anywhere.”

Mellinger realized that she never had to take no for an answer.

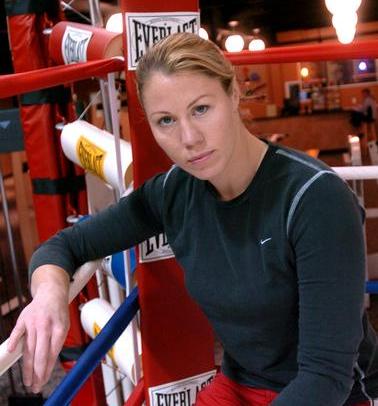

Leah Mellinger throws a punch during a workout in 1998.

JOHN WALK | Features Writer

JOHN WALK | Features Writer

ANDREW KOOB | Staff Writer

ANDREW KOOB | Staff Writer